The Zone of Interest (2023)

Glazer’s Zone of Interest, a story about the domestic life of Rudolf Höss, Auschwitz commandant, and his family who live immediately next door to the death camp, is a disturbing and thought-provoking movie. In treating the Holocaust as something happening off-screen, he puts the audience in the same position as the Höss family: we already know exactly what is going on on the other side of the garden wall, and we can choose how to respond to it.

It should be noted that Glazer makes two assumptions about the audience for this film. First, a fairly safe bet, is that they already know the key facts about the Holocaust and what took place in Auschwitz and other camps like it (though doubtless there will be some who don’t); second, that they will use their imaginations “correctly” to fill in what is unseen and, in some ways, unimaginable. This is the greater gamble. Whilst I have read books on the subject, seen other movies and watched dramas and documentaries, (very recently, Schindler’s List) and have developed both a broad understanding of the events of that time, I have also built a degree of resistance to the emotional distress of the horror, which I would regard as a natural defence mechanism. One cannot be filled with bottomless despair every time one encounters it.

Glazer may expect me to reimagine and to respond appropriately; to fill in the gaps in the narrative and give the film an emotional resonance that otherwise would be missing. But to attempt to recreate scenes in my imagination which can only pale in comparison to the real thing is futile. Glazer must know this, so is he instead aiming at something else? This is not a story about what is happening inside the camp, which is why he doesn’t want to show us.

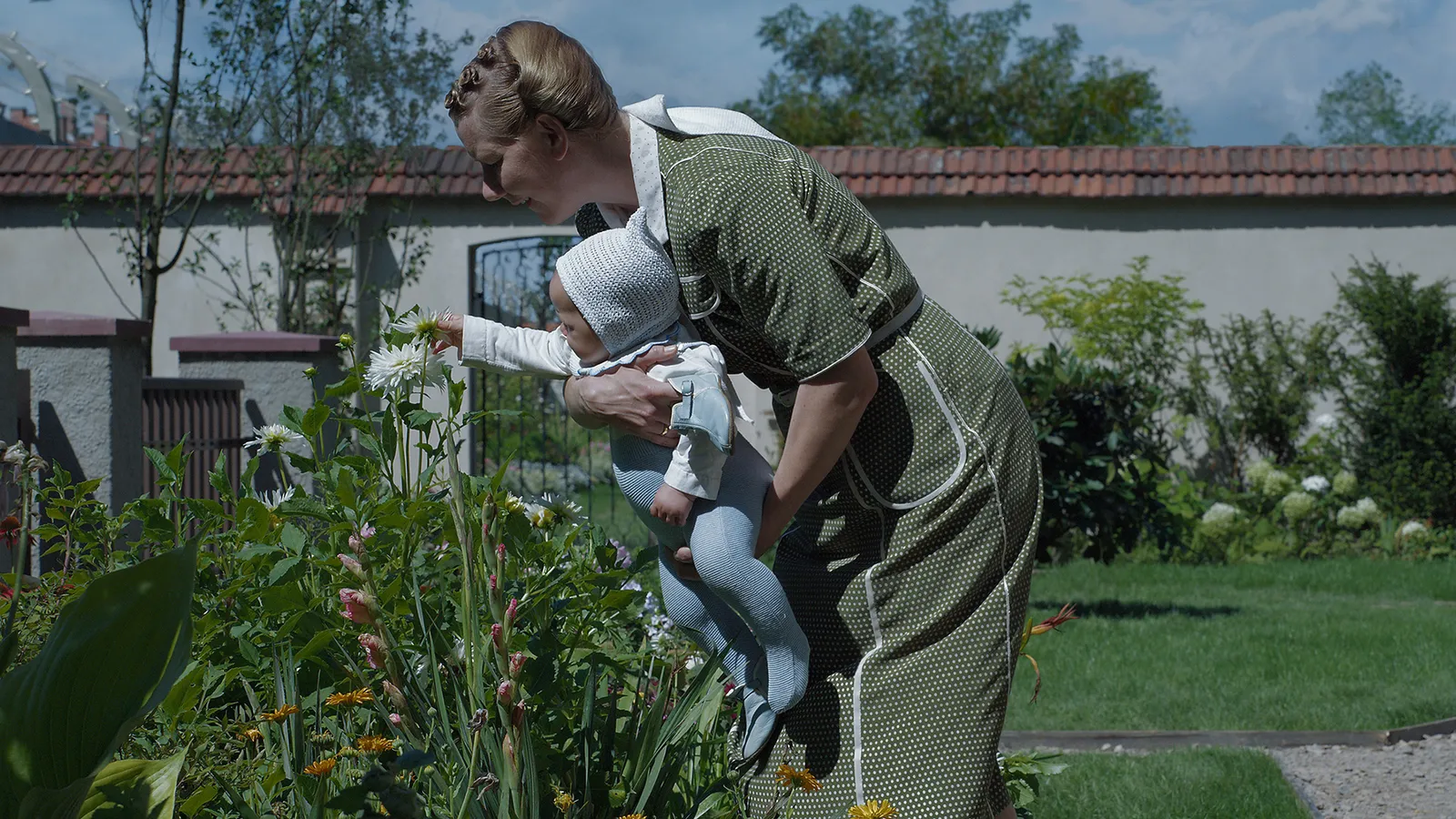

Instead of trying to elicit a sense of horror at what is happening over the garden wall, we must deal with what we do see, only filling in with the fact of the Holocaust and not its details. And what we see and hear (in the dialogue) gives us more than enough evidence that the adult characters portrayed are pathologically incapable of empathy and their children psychologically damaged by their upbringing in such bizarre circumstances. Their daily lives are full of the ordinary – eating, dressing, sleeping, playing, swimming, dreaming, chatting – and that makes them just like us. But the circumstances in which they act out their ordinary lives are extraordinary, and we who are distanced both by history and, most likely, lives and circumstances that cannot compare with theirs, surely must judge them inhuman without having to manufacture an emotional response.

The expression, “the banality of evil” is often used to help us recognise that unspeakably evil acts can be carried out by people who otherwise lead ordinary lives; they are not the monsters and demons of myths and legends, but maybe the next-door-neighbours, the shopkeepers, the policemen and teachers, the gardeners and labourers, the secretaries and hairdressers. Perhaps Glazer wants us to become more perceptive in our judging of people. We don’t need to look over the garden wall into the abyss. In fact, if we choose to, we’re already too late. One reading of a scene of banality near the end confirms this. We see the cleaners busy at the Auschwitz museum, sweeping the floors trodden by so many doomed people, polishing the machinery of extermination, and the glass behind which we see the piles of discarded shoes for which Auschwitz is so gruesomely notorious. The question is posed, are we seeing a scene of the memorialising of the dead? Or, since the cleaners can carry on such mundane tasks in the constant presence of horror, are we becoming so inured to the lessons we should be learning from the Holocaust that we will fail…are already failing…to prevent similar horrors? The objection to “equivalence” (it is deemed by some unacceptable to draw parallels between the Holocaust and present-day conflict, murder, torture, slavery) is that it diminishes the enormity of the genocide of the Jews. But while we must never forget not just the fact of the Holocaust, but the details, we must be alert to the similar capacity for evil that we can see in the horrors of the present day. For us, the “zone of interest” is what we must pay attention to outside the history of the Holocaust, in the here and now.