M*A*S*H (1970)

What seemed a hilarious hoot back in 197-...whenever I first saw this...now seems much less so. I watched this last night (30/01/21) and found it disappointingly unenlightened, especially with regard to sexism. Perhaps my expectations were too high. After all, the preceding decade may have seen the flowering of women's liberation, but mainstream culture in the Sixties and Seventies was very tolerant of prejudiced attitudes. We may still have our own decades problems to deal with, but the lens we view humour with now is more sensitive to discrimination.

However, it wasn't just the sexism that demands a reappraisal, but the overall narrative thrust: what on earth was it "about"? Altman's quasi-documentary approach, where so much is long or medium shot, and with overlapping 'realistic' dialogue creates a narrative that is more episodic eavesdropping. The fact that so much of what is viewed is set up for comedic effect does not mean that Altman's realism is any less valid than, say, Spielberg's realism at the beginning of Saving Private Ryan*. Colonel Blake's conversations with Radar, or Duke's with Hawkeye are both as important and inconsequential as the surgeon's chat as they saw broken bones and sew torn limbs. A very few scenes are more carefully, even blatantly stylised, such as the Last Supper, prior to Painless' intended suicide. Was it just visual fun, or an opportunity for sacreligious parody, in keeping with the characterisation of Rene Auberjonois' padre, a figure of fun who blesses everything that moves (literally, when we see him blessing the jeep that Hawkeye is going to leave in at the end) and fails to confront the docs when they broadcast Hotlips' and Burns' lovemaking grunts around the camp? It's difficult to claim that this was about inherently decent medics understandable wayward behaviours in the face of the horrors of war when the horrors are downplayed (the victims are faceless mangled bodies, wrapped in so much bloodied sheeting, and see so fleetingly that they barely register) and the medics are shown in so determinedly an amoral light that such an argument wouldn't stand much scrutiny.

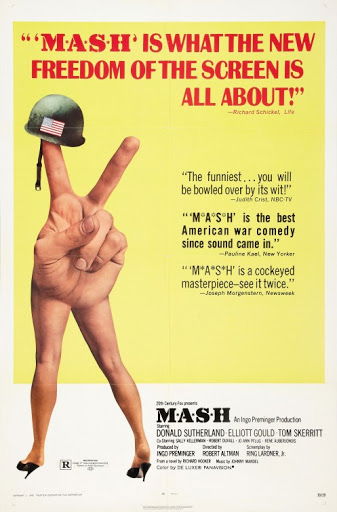

Basically, the two-fingered salute on women's legs on the film poster sums up the story: it's a prolonged anti-establishment diatribe, with anything and everything up for comedic criticism, and no-one character or idea on offer as a redeeming antidote to the merciless lampooning. It obviously resonated with Vietnam-weary audiences in 1970, but now seems somewhat messy and trivial.

(*This realism might be regarded as justifying the sexism, because we might be willing to accept that that's how things were back then. Other critics have pointed out that the 'credits' recap of characters at the end, where Sally Kellerman is seen naked in the shower again, is unnecessary, and undermines any claim that Altman might have made that he wasn't endorsing outdated male attitudes to women.)