Un Chien Andalou (1928)

An extraordinary film with bizarre images and no conventional narrative, it must have been quite shocking to audiences of the time, assuming any conventional audience went to see it! (It had a limited showing at first, in Paris, but did run longer than anticipated.)

How should one react to a film which sets out so clearly to be 'not film'? By treating it as a visual puzzle and a minor thesis on surrealism.

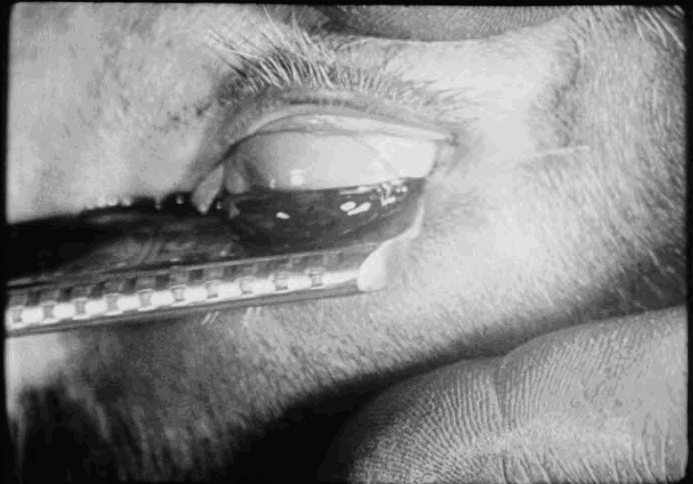

It's quite absorbing, despite, or perhaps because of the lack of any 'plot'. Each short sequence of events, tenuously linked, leads you to wonder what will happen next, and given the disturbing nature of the images - the ants emerging from a hole in a hand; the severed hand; the cutthroat razor slicing through an eyeball - there is some tension in that wondering: how are we to be shocked next?

It's all too easy to dismiss this as a piece of nonsense, without bothering to probe further: producers Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel are just having a laugh at our expense, challenging us to ask about the significance of what we see (and hear, as the original soundtrack has been deliberately selected too for some purpose; soundtrack revisions are mystifying) when it might mean nothing at all. But if we set aside pride and attempt to make some sense of the film, we can at least see that the creators were taking typical cinematic conventions and subverting them. For example, the use of intertitles is absurd, starting with the first ("Once Upon A Time"), inviting us to think we are about to see a fairytale, and then later titles deliberately upsetting any sense of chronology. We are presented with one saying 'sixteen years later' in the middle of a scene that seems a continuation of what went before.

What unfolds is certainly a fantasy of some kind, with the man in the opening scene sharpening his razor, then gazing at the moon, as if in some kind of reverie. From that single point of 'reality' onwards, one could argue that all else is a dream, and the conventions of editing to simulate storytelling are shown to be fake.

Are Dali and Buñuel treating us as a gullible audience, tricked into accepting a single, increasingly naturalist approach to movie-making, most notably dominated by American narrative cinema; and now, that approach is exposed as being no more 'reality', than the surreality of our dreams where, for example, the juxtaposition of events allows us to be simultaneously an observer and a participant, where time is elastic and where images, palces, people merge and separate, acquiring this meaning here and then another meaning elsewhere.

Yes, this does belong in the pantheon of unmissable movies, not least because so many later movies paddled in the shallow end of surrealism while Un Chien Andalou dived headfirst into the deep end. Many cinema goers will shy away from something as blatantly unorthodox as this, but many who enjoy mainstream horror and fantasy movies (David Lynch, David Cronenberg and Stanley Kubrick spring instantly to mind) that owe as much to Buñuel's essay as they do to Shelley, Stoker, Stevenson and the Universal cycle of horror.